Category Archives: Uncategorised

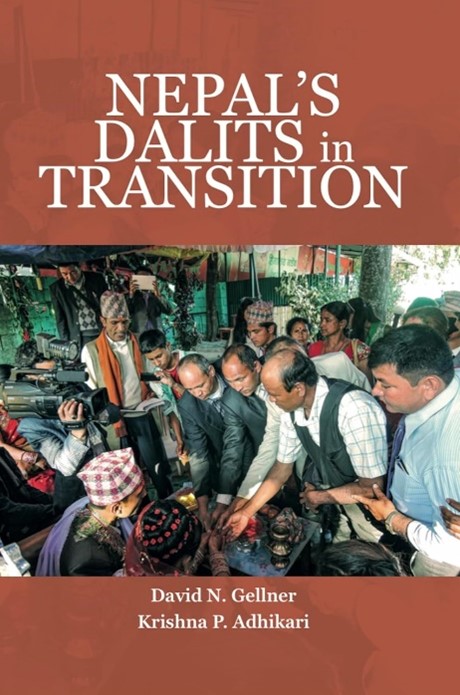

Nepal’s Dalits in Transition

5th November 2024

DSN UK is proud to present the following Book with 368 pages published on 2nd April 2024. Join us in our vision to create a world without Caste Discrimination

About the Book

For too long Nepal’s Dalits have been marginalized, not just socially, economically, and politically, but from academic accounts of Nepalese society as well. This volume forms part of a welcome new trend, the emergence of Dalit Studies in Nepal, led by a new generation of Dalit scholars. It covers a wide range of issues concerning Nepal’s Dalits and offers a snapshot of the advances that they have made—in education, in politics, in the bureaucracy, economically, and in everyday relations. At the same time the book documents the continuing material disadvantage, inequality, discrimination, both direct and indirect, and consequent mental suffering that Dalits have to face. It also touches on the struggles, hopes, and dilemmas of Dalit activists as they seek to bring about a new social order and a relatively more egalitarian society. Nepal’s Dalits in Transition will be essential reading for anyone interested in the past, present, or future of social change in Nepal.

Editors: David N. Gellner is Professor of Social Anthropology and a Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford; Krishna P. Adhikari PhD (University of Reading) is an expert on social change and development in Nepal and elsewhere, and a Research Affiliate of the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford.

Contributors: Krishna P. Adhikari * Tilak Biswakarma * Arjun Bahadur BK * Steve Folmar * David N. Gellner * Raksha Ram Harijan * Sambriddhi Kharel * Ram Prasad Mainali * Purna Nepali * Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka * Krishna Shrestha * Manoj Suji * Ramesh Sunam.

Published by a Kathmandu based publisher: https://vajrabookshop.com/product/nepals-dalits-in-transition/. Available via. Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Nepals-Dalits-Transition-David-Gellner/dp/9937624363/

The Black History Month 2024

30th October 2024

The United Kingdom first celebrated the Black History Month on 1st October 1987, and it was recognised as the African Jubilee which coincided with the 150th anniversary of the Caribbean emancipation. This year’s theme, ‘Reclaiming Narratives’, is very powerful indeed as it emphasises the importance of story telling from the perspective, experience and memory of the Black People. Reclaiming narratives enables to unfold the past in truth and honesty for the benefit of the present to build a better future. Narrative plays a key role as it differs from Story telling by choosing how to tell a story.

The Windrush scandal speaks volumes as it is still grappling to get justice for those affected. Although the Windrush Compensation Scheme has been beneficial, it needs to reach those that are yet unable to claim it. The homelessness category embraced specially by this compensation scheme will hopefully target those in the margins as it says, “Changes made to the Homelessness category, including the removal of the cap, and removal of the requirement to demonstrate physical or mental health impacts due to homelessness. These changes will make sure people are compensated for the full period they were homeless.”

In this juncture, DSN UK endorses its support to reclaiming narratives as we believe that the Dalit Liberation Movement was able to move forward in history by consciously validating and empowering those engaged in Dalit Liberation through Dalit Sahitya (literature) that focuses on the lives, experiences, and the struggles of the Dalit communities to liberate themselves along with those who oppress them based on caste. The Black History Month website rightly observes, “For too long, the history of Black communities has been told through lenses that often misrepresent, oversimplify, or entirely overlook the rich and diverse experiences of those who lived it.”

DSN UK wants to reiterate that although the Black History Month ends tomorrow – 31st October for this year, our commitment and journey together for freedom continues until everyday racism and casteism is wiped out, until the last person in bondage and discrimination is liberated. Narratives reclaimed will ensure what the Black people want to be share to reclaim not just their narratives but their genuine identity of who they were in history, what are their contributions despite being enslaved and their vision as to why do they want justice. The yearning and hope for reclaiming identities and experiencing life in all its fulness will help us move forward together to realise our dream for a better tomorrow for every human being in this world.

Dr Elizabeth Joy

Director DSN UK

30th October 2024

We are recruiting!

14th May 2024

We are recruiting for a new Director and Office Administrator.

The Dalit Solidarity Network is a small human rights organisation working to eliminate caste-based discrimination in the UK and South Asia.

Director:

We are now seeking a part-time Director for 3 days/week to: develop and deliver of DSN-UK’s overall strategy and objectives; provide strategic leadership to influence the policy and practice of key stakeholders to further DSN’s vision of a ‘world without caste discrimination’; and to lead overall management of DSN-UK, including management of DSN-UK staff, its finances and other resources.

London-based but hybrid-working arrangements (from home and on site) will be considered. Deadline for applications: 13 June 2024.

Please apply at: The Guardian or CharityJob

Office Administrator:

We are now seeking a part-time Office Administrator for 2 days/week, initially for one year with a possibility of renewal.

London-based but hybrid-working arrangements (from home and on site) will be considered. Deadline for applications: 13 June 2024.

Please apply at: CharityJob

Training Session on Caste-Based Discrimination in UK Business and Global Supply Chains

23rd August 2023

In July, Dalit Solidarity Network UK hosted two events on caste-based discrimination in UK business and global supply chains, in collaboration with Ethical Trading Initiative, School of Advanced Study at the University of London, International Dalit Solidarity Network, and National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights.

A training session on caste-based discrimination in business and supply chains was held on July 13th. We were joined by representatives from 9 different UK based businesses with supply chain links in caste affected areas. The training was targeted at enhancing the company’s ability to detect caste-based discrimination in these work place settings both in-house and within the supply chain. As well as exploring potential strategies for addressing them going forward in their work. Those in attendance heard from DSN UK Director Gazala Shaikh, and Chair Corinne Lennox, alongside ETI’s Hannah Bruce and Beena Pallical of the Asia Dalit Rights Forum.

This was followed by a dissemination meeting on July 18th, where we were able to share experiences and discuss future strategies. Here we were also joined by Manjula Pradeep and Peter McAllister. Manjula is a leading human rights activist in the area of Dalit rights, with a special focus on Dalit women. Those in attendance had the privilege of hearing a very inspiring talk from Manjula about her work surrounding Dalit rights in India and view her film Dalit Defenders: United in the struggle for dignity and justice. Peter is the Executive Director at Ethical Trading Initiative, with over 20 years of experience in international development and rights-based initiatives around the world. He shared with us his knowledge and strategies for recognising and addressing discriminatory practices in business and supply chains.

Both events were made possible through the grant support of Knowledge Exchange Fund of the University of London.

To watch the discussion session from July 18th follow the link below:

Amnesty India, Oxfam India, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative and even Mother Theresa’s established charity all suffer from withdrawal of foreign funds

18th January 2022

On Thursday 6 January, Lord Harries of Pentregarth, Co-Chair of the APPG for Dalits, tabled a Parliamentary Question ‘To ask Her Majesty’s Government about what representations they have made to the government of India about the blocking of overseas funds for the Missionaries of Charity and other non-governmental organisations’.

India’s Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) appears to have been used to hinder many NGOs from operating within the country. This Act in effect requires that any NGO that receives income from abroad is registered with the government with a registered bank account in Delhi – wherever they maybe be located. However, accusations have been made that it is being used to silence a number of civil society voices that have criticised the current government. Many have heard about the problems that Oxfam India and Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity have had, but there are 179 NGOs whose licence renewal has been denied, not to mention those that have apparently not been renewed due to going past their expiry date, and some organisation’s bank accounts have been frozen. Support from abroad for minorities, who may receive limited funding within India, is absolutely essential.

It is heartening, therefore, to see Lord Harries table this parliamentary question and raise the issue of certain minorities being targeted under the legislation. Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon stated that he was well aware of the difficulties, and that officials have discussed both with the British High Commission in Delhi and the Indian Government itself, and that they will ‘continue to monitor developments in this respect’. He added that Christian, Muslim and Hindu organisations were also on the list, and that he was seeking more information.

The subject of caste discrimination was also raised by Lord Collins of Highbury and Lord Hamilton of Epsom, who asked how caste discrimination was compatible with human rights. Lord Ahmad himself brought up the Dalit community, and it was positive to see that this marginalised group is being considered in discussions.

To see a full transcript of the debate, you can find it here.

Several days later, Catherine West (shadow minister Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs) asked in the House of Commons what discussions had been had with the government of India on their refusal to renew Oxfam India’s licence. The response from Amanda Milling was somewhat disappointing, merely stating that she was aware of the difficulties, and that where there are concerns, they are raised directly with the Indian government, adding that the British High Commission in New Delhi ‘will continue to monitor developments, and engage with religious representatives and run projects supporting minority rights’.

It is essential that the British government receive assurances that there is no political motive behind the refusal of licences under the FCRA. Those who are suffering most through India’s decisions are Indians themselves, particularly those who have little access to support and justice.

The House of Lords addresses key issues for Dalits and Tribals in Nepal

17th December 2021

Representatives of the APPG for Dalits have been hard at work again, this time on the position of Nepal. Lord Harries of Pentregarth asked ‘what progress [the UK government] have made towards their commitments to providing (1) health services, (2) water and sanitation, and (3) access to justice, for marginalised communities in Nepal, including Dalits and Adivasis’.

Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon answered on behalf of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), stating that the UK targets development support at the most marginalised communities, and provides support to the Ministry of Health to ensure the most vulnerable are covered. He added that in 2021 they changed their support structure so that 400,000 of those most at risk were provided with water, sanitation and health facilities.

Lord Harries then asked the Minister as to why no Dalits had been appointed to the National Dalit Commission or the new National Human Rights Commission. The response was that there were encouraging signs of progress, as in 2017 roughly 22% of locally elected government positions were held by Dalit communities. However, Lord Ahmad agreed that the government will continue to lobby on strengthening human rights.

Lord Alton of Liverpool pressed again on the lack of representation of Dalits themselves on the National Human Rights Commission and the National Dalit Commission, and asked whether this would be specifically raised with the Nepalese government. He also asked whether there were any figures on the percentage of Dalits and Adivasis who have been vaccinated against COVID-19, and indeed the death rates compared to the rest of the population. It was confirmed that 24% of HMG’s support targeted vulnerable groups, including Dalits, but no further figures were forthcoming.

Lord Collins of Highbury asked whether, during the Prime Minister’s special envoy’s visit to Nepal to discuss girls’ education, representatives of the Dalit community attended. The response was that all communities were involved. Baroness Armstrong of Hill Top also asked about the UK aid programme now that cuts have been made to funding, stressing that the Strengthening Access to Holistic Gender Responsive and Accountable Justice (SAHAJ) programme had been very successful, particularly with women and girls from the Dalit community, but that their future was now in financial jeopardy. Baroness Armstrong added that the VSO (who run the SAHAJ programme) need to know whether finances will be provided, in order to effectively work with its partners in Nepal. Lord Ahmad replied that he was in direct contact with VSO, appreciated their valuable work, and would look into it very closely.

Our thanks go out to the APPG for Dalits for continuing to keep caste-based discrimination on the agenda and ensuring that the government is held accountable for bringing up difficult subjects with their counterparts overseas.

DSN-UK’s Annual General Meeting 2021

19th November 2021

This year’s AGM was a relatively quiet affair, though that’s not to say that there wasn’t plenty to be dealt with. Apart from the usual matters of adopting the proposed Annual Report and Accounts for 2020/21, we were delighted to welcome Dr Prerna Tambay to our Board of Trustees. Prerna is an active leader in the Dalit movement, and already a long-standing member of DSN-UK, having contributed to past AGMs. Her specialisation is digitalisation and mobilisation, and she has a particular interest in women’s issues. We were also pleased that Corinne Lennox (Chair), Kate Solomeyina (Treasurer) and Ramani Leatherd were re-elected to the Board, so that the transition period between Directors can continue smoothly.

Our membership numbers have continued to increase, although raising awareness of all aspects of caste discrimination is an ongoing issue, and we are often preaching to the converted. However, the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Dalits has been working hard to keep caste on the agenda. Members have tabled parliamentary questions and debates, including one on Human Rights in India, following the new bilateral trade agreement.

Unfortunately, our Everyday Casteism project hasn’t been as successful as we would have liked, so DSN-UK is currently working on direct outreach to Higher Education Institutions. Meanwhile, our work on Human Rights and Business remains as important as ever, and through IDSN we have a great relationship with a lot of the UN Rapporteurs, ensuring that casteism is considered in global supply chains.

The AGM had the pleasure of listening to M. Savio Lourdu from India discussing a litigation case that he is working on, which highlighted the problems of reservation in local elections, and how power is still being abused by the ‘dominant’ castes in communities. Furthermore, he asked the network to ensure that in any discussions between India and the UK, we make sure that our voices are heard over ongoing human rights abuses.

While the pandemic has affected funding for many charities, it is important to remember that at the grassroots level, Dalits have suffered disproportionately. DSN-UK is proud of our achievements over the last year, and the support of our trustees, patrons, funders and members has been invaluable.

If there is one thing you can do to help the movement, please remember to use the term ‘safe distancing’ rather than ‘social distancing’. Dalits have experienced several thousand years of ‘social distancing’ already!

A virtual screening of ‘I Am Belmaya’ with a unique Q and A session

12th October 2021

On Wednesday 6th and Thursday 7th International Dalit Solidarity Network, along with Tideturner Films, organised a virtual viewing of ‘I Am Belmaya’: a documentary made by Sue Carpenter and Belmaya Nepali about Belmaya’s journey to become a film-maker, centred mainly in Nepal.

Belmaya is both female and Dalit, and the intersectionality of these two aspects have held back her progress in life. Her father died of cancer when she was young, her mother of suicide sometime later, and she ended up in a children’s home. Her education was cut short by the lack of empathy towards her, with the teacher accusing her of having a head full of cow dung. Consequently, she married early and soon had a daughter to raise. Doing back breaking work in construction, unhappy in her marriage and desperate to ensure that her daughter had a good education, Belmaya took the opportunity to learn how to make films after experiencing the joys of photography whilst in the children’s home.

The story of how she became the role-model she wanted to be for her child, and her newfound ability to tell the stories of those who are most marginalised in Nepalese society, make for a wonderful and incredibly moving film. Mentored by Sue Carpenter, the film’s co-director, and other teachers later in life, it is clear that Belmaya has been given an opportunity that few in her position are offered.

The audience were treated to a unique Q and A session with Sue and Belmaya, assisted by translator, Bishu. The range of questions were wide – covering what she still has to learn as a film-maker, the difficulties over her poor education, Nepalese society’s view of women and her hopes for the future. Perhaps most heartening was the potential offer of work from those participating in the Q and A, giving Belmaya the chance to increase both her skills and her earnings. Sue has obviously been an incredible source of strength during this time, working hard to make sure that Belmaya and the film get the recognition that they deserve.

It was a genuine pleasure to see ‘I Am Belmaya’, a film which gives a heartening glimpse of how caste and gender can be overcome with determination and the right help. To find out more about the film, go to: I AM BELMAYA – Taking the Camera and Power into Her Hands.

The Californian Democratic Party adds ‘caste’ as a protected category

7th September 2021

The Californian Democratic Party has set a precedence on the issue of ‘caste’ by adding it as a protected category to their Party Code of Conduct. Despite heavy opposition from a number of Hindutva organisations in the US (including the Hindu American Forum), activists have succeeded in persuading the Party that caste-based discrimination is a genuine cause for concern and that action should be taken to ensure that victims have access to justice.

Caste hit the headlines in the US back in 2020, when the State of California took Cisco Inc. to court over the discrimination that one of its engineers had suffered in the workplace. It wasn’t long before a host of complaints from employees of other Big Tech companies in Silicon Valley was brought into the public domain, consequently shining a light on this hidden issue. Twenty-two campuses from the University of California decided to add ‘caste’ as a protected characteristic earlier this year, which seems to have propelled a political interest.

Amar Singh Shergill, a California Democratic Party Executive Board Member and Progressive Caucus Chair, announced: ‘With the addition of caste protections to our Party Code of Conduct, the Democratic party recognises that California must lead in the historical battle for caste equity and ensure we acknowledge the need for explicit legal protections for caste-oppressed Americans. We understand that protection from caste-discrimination may be accessed under pre-existing categories of ancestry, religion, and race, yet many caste-oppressed people do not report discrimination because this explicit legal protection is not yet widely recognised. Like previous struggles to add protections for gender identity and sexual orientation, we believe adding caste protects all Americans. We are ensuring the most vulnerable know we value their rights. We hope our additional will inspire other institutions to bring remedy to the issue of caste discrimination in the US, and urge all other state Democratic Parties to follow.’

Amnesty International USA, Equality Labs and the Indian American Muslim Council have all come out in support of this addition, along with a host of Ambedkarite organisations and human rights groups.

Undoubtedly, this is great news and indicates the first political recognition of casteism within the US. However, time will tell if this will be an effective launching pad for both ideological and legislative change. One would hope that New Jersey, also a Democrat-held State, will soon follow suit, considering its own problems after a recently built BAPS Hindu Temple was found to have employed Dalits as forced labour. Yet reacting to a problem on your own doorstep is never as efficient as preventing one. It would be a remarkable step forward if other political parties from all over the US would enact this type of change before it was actually needed. This would send a clear message that caste-based discrimination has no place in American culture, and that other countries should follow suit.

The UK House of Lords debate on India and Human Rights

13th August 2021

On 22 July 2021, Lord Harries of Pentregarth (Co-Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Dalits) opened a debate in the House of Lords on India and Human Rights. Whilst expressing his enormous admiration for those in India, and appreciating their long history of discussion and debate, he also raised his sadness over the rise of nationalism and increasing denial of fundamental human rights.

Aside from the lack of academic freedom, Lord Harries mentioned the targeting of journalists; human rights groups who have had bank accounts frozen and been denied travel visas; Muslims who have suffered attacks stemming from an anti-Muslim Hindutva policy and their lack of inclusion in the new terms of the Citizenship Amendment Act; Christians who have tried to escape the stigma of being ‘untouchable’; and Dalits. Lord Harries was keen to point out that while the Indian constitution is in many ways admirable, including its emphasis on equality for all, being born into ‘untouchability’ is worse than slavery and requires more than legislation to remove it. Dalits suffer disproportionately by every indicator, and as many are bonded or day labourers, they are particularly vulnerable to abuse and a lack of access to justice. Currently there are 24 Dalit activists being detained under anti-terrorism laws, and this is unacceptable.

India is on the UN Human Rights Council, and as such, it must be held to certain commitments. He urged that submissions should be made at the highest level to encourage change.

Lord Parekh and Baroness Verma both acknowledged that there were some issues that still needed to be considered, including the treatment of Dalits, but warned that with such a large population, incidents were inevitable and that the situation should not be exaggerated. Lord Parekh pointed out that while independent India has adopted positive discrimination, there is still a long way to go and that there needs to be a greater sense of urgency. However, while India welcomes critical advice, it should be accompanied by humility and based on a sympathetic understanding of India’s culture. Baroness Verma added that over the last seven or eight years the government has embedded policies to improve equality, particularly for women, including protection from the Muslim Triple Talaq divorce law. However, she argued that the UK has a habit of ‘lobbing charges into India without contextualising the progress that has been made’, and that when pointing fingers, we have our own prejudicial barriers. Baroness Verma criticised the number of commentaries coming from the House of Lords without providing evidence of the accusations being levelled, and voiced her concern that many of the comments were inflammatory.

Lord Hussein agreed that the current human rights record ‘paints a very dark picture’ in some areas, with daily life for Muslims and Christians becoming a daily struggle under the Hindutva far-right influence. The violence against the Dalit community never seems to end and he questioned why India has not been mentioned in the Foreign & Commonwealth Office’s latest report on Human Rights. Lord Singh added that under the current government, with its desire to become a Hindu state, Muslims and Dalits continue to suffer brutality.

The Earl of Sandwich, Lord Cashman and Lord Collins of Highbury expressed that it was important that as friends of India we should be able to speak out much more often and more loudly. Despite the deterioration of Human Rights, India has shielded itself from international criticism due to its economic prospects and the desire of other countries to solidify trade agreements. Lord Cashman in particular wants reassurance from the UK government that when strengthening its ties, it ensures that there are human rights clauses included within any agreement, while Lord Collins asked what would be done to end violence against Dalit Women.

Lord Alton quoted Dr Ambedkar, one of the founding fathers of India’s constitution: ‘If I find the constitution being misused, I will be the first to burn it.’ Again, the denial of rights to Dalits, despite this constitution, and the dubious sedition laws being used to arrest and detain opposition voices was mentioned. Though he praised the British High Commission project to provide legal training for women his concern was that the high levels of rape perpetrated against them was not given enough significance. Furthermore, Covid has had more impact on Dalits as bonded or daily labourers, further deteriorating their well-being. This was also cited by Baroness Northover, along with her concern that the FCDO has not taken this into account when looking at funding. It was also noted that Freedom House has downgraded India to being only ‘partly free’.

Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon, Minister of State for the Commonwealth and United Nations at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, responded to the questions by stating his credentials as both the minister responsible for relationships with India and the Minister for Human Rights. He agreed with Lord Parekh and Baroness Verma about the UK’s relationship with India and its importance, and stated he has engaged in candid discussions with his counterparts. At the G7 partners committed to tackle all forms of discrimination, and media freedom plays an important role in that. However, everyone recognises that human rights work is never done. This month the 2020 Human Rights and Democracy Report from the FCDO was published and the UK has stepped up its efforts all over the world, including in its close collaboration with India to provide oxygen during the Covid pandemic. He added that just because a country is not specifically mentioned in the Human Rights Report, it doesn’t mean that these issues are not raised with the relevant countries. Furthermore, the Foreign Secretary has raised a number of issues, including the position of Kashmir, minorities communities and religious communities. They have also asked for Amnesty India’s funds to be unfrozen in order for them to continue their crucial work. Meanwhile the government’s ‘recent project work with the Dalits has included the provision of legal training for over 2,000 Dalit women to combat domestic violence and the creation of the first ever network of Dalit women human rights defenders trained as paralegals.’ Lord Ahmad concluded by assuring the other members that the UK government would continue to engage with India on various issues, including trade, of which human rights will remain a central part.